In India filing a complaint or an FIR is not simply a procedural requirement, it is the first legal step in the initiation of the criminal justice system. Despite the significant importance of making a complaint or FIR, many citizens are unaware of what laws apply to this process and state procedure. The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) provides for two types of reporting of an offence: a “complaint” under Section 2(d) and a First Information Report (FIR) under Section 154. Each has its own legal consequences and processing procedure depending upon whether the offence is a cognizable or non-cognizable offence.

In some landmark cases, such as Lalita Kumari v. Govt. of Uttar Pradesh, the Supreme Court of India has held that it is compulsory for the police to register an FIR in cognizable offences. The act of police refusing to file an FIR infringes constitutional protection under Article 21 (Right to Life). There are also statutory remedies when police refuse to register a FIR. For example, Section 154(3) and Section 156(3) CrPC.

Complaint vs. FIR- What’s the Difference

On the surface, complaint and first Information Report (FIR) are words with similar meaning, however, under Indian criminal law the meaning of complaint and FIR is clearly defined, and the requisites for both are governed under different sections of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC).

Section 2(d) of the CrPC defines complaint: as follows:

Complaint means any allegation made orally or in writing to a Magistrate, with a view to acting under this Code, that some person (known or unknown) has committed an offence. Police report is not included in complaints. The offence for complaints only includes non-cognizable offence which means that a Police Officer cannot arrest the accused without the prior approval of a Magistrate. Examples of non-cognizable offences include but not limited to defamation, public nuisance or simple hurt.

FIR on the contrary is defined under Section 154 of the CrPC caries serious consequences for the Police in that FIR relates to cognizable offences which are serious in nature including but limited to, murder, rape, kidnapping or robbery in these cases, police are enabled and bound to register the FIR, investigate the concern, and arrest the accused without even seeking pre judicated approval.

The major difference lies in:

- Nature of the offence; cognizable or non-cognizable

- Legal consequence; FIR will result in investigation whereas complaint may not always lead to an investigation.

- Authority to be approached; police for filing FIR and magistrate for complaint.

Understanding these differences is very crucial before starting the legal process, as wrong type of report could lead to delay in justice.

| Factor | FIR | Complaint |

|---|---|---|

| Applicable law | Section 154 CrPC | Section 2(d), 200 CrPC |

| Offence Type | Cognizable | Non-Cognizable |

| Who to Approach | Police | Magistrate |

| Can arrest follow immediately? | Yes | No |

| Leads to Investigation? | Yes | Not always |

| Signature Requirement | Required | Required |

| Legal Consequence | Mandatory Police Action | Discretionary Judicial Action |

Who can file FIR or Complaint?

Anyone can file an FIR or Complaint. As provided in Section 154 CrPC, any person aware that a cognizable offence has occurred may file an FIR. A cognizable offence may be reported by any individual:

- The victim

- A relative of the victim

- A witness

- Any party with knowledge of the cognizable offence, whether direct or indirect

Similarly, a complaint, as defined in Section 2(d) CrPC, can be made by any person before a Magistrate for both cognizable and non-cognizable offences, except where a police investigation has already occurred.

Most importantly, even a minor or a person who has not been directly affected by the crime (e.g., a social worker, journalist) can set the process in motion.

Why File FIR or Complaint?

Whether you file an FIR or complaint, it is the first lawful step in starting criminal proceedings and recording your offence.

- FIRs are related to cognizable offences (such as murder, dacoity, and rape) which require immediate police investigation. These offences are addressed in the BNS under Sections 101-109 (which link back to IPC sections 302, 375, and so on), and require police investigation, and authority to arrest without access to the magistrate to seek permission.

- Complaints are concerning non-cognizable offences (such as public nuisance, defamation, simple hurt) which are under BNS Sections 356-358 when the police officer must first obtain the permission of a magistrate before proceeding.

If the FIR or complaint is filed late, it may mean justice delayed, loss of evidence, or worse, the victim has overlooked a shield of protection under Acts, such as the Witness Protection Scheme, 2018.

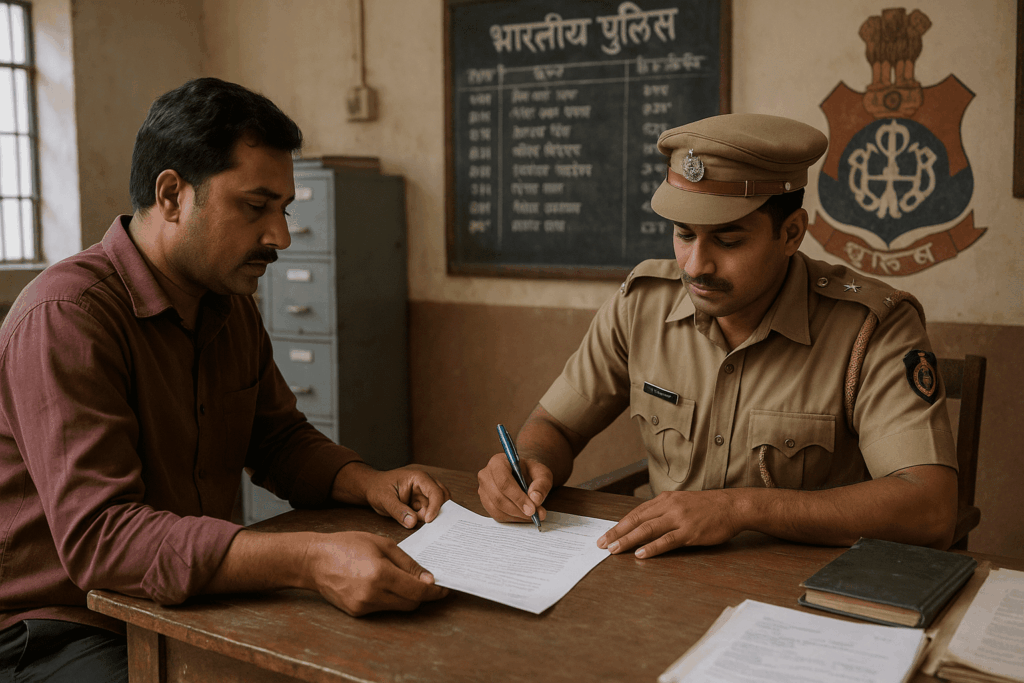

How do you file FIR or complaint?

FIR:

- Visit the nearest police station

- Provide the police with oral or written information

- In accordance with Section 154(1) CrPC the police will write it down, read/write it back to you and take your signature

- You must be given free copy of the FIR (Section 154(2) CrPC)

- Some states allow e-FIR filing for minor offences (i.e., theft, lost property)

Complaint:

- File a written complaint before a Judicial Magistrate (First Class) under Section 200 CrPC

- The Magistrate may record the statement of the complainant under oath

- In case of non-cognizable offences, Magistrate may direct the police to do investigation under Section 202 CrPC

Legal Consequences

When an FIR is registered with the police under Section 154 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, the police are obligated to investigate the allegation of cognizable offence. The police must gather the evidence, arrest the accused (without the permission of the Magistrate in cognizable matters), and provide the charge sheet under Section 173. In this way, the FIR has led to action and the subsequent steps will usually initiate a criminal case.

A Complaint is submitted in terms of Section 2(d) of the CrPC to a Magistrate. A complaint is submitted, often in terms of non-cognizable offences or when police are not available immediately. A Magistrate may examine the complainant and witnesses to consider acting under Sections 200 and 202. It may be determined whether the Magistrate will take cognizance of the alleged offence. If the Magistrate is satisfied with the complaint, he may act by way of summons or direct an inquiry. In this way, the police-led investigation is commenced by an FIR, and a Complaint will begin a court/magistrate-based process which may or may not involve police at a later time.

Remedies in case of Refusal

If police refuse to register an FIR in case of cognizable offence, then the aggrieved person may approach with a written complaint to the Superintendent of Police (SP) under Section 154(3) CrPC. If the SP does not act either, then aggrieved person may file a complaint before a Judicial Magistrate under Section 156(3) CrPC with a prayer to direct the police to register the FIR and investigate. Moreover, it is explicitly held in the Supreme Court in Lalita Kumari v. Govt. of U.P. (2013) that the registration of FIR is mandatory in case of cognizable offences.

If, after a preliminary examination of a Complaint, a Magistrate dismisses the Complaint under Section 203 CrPC, the complainant may seek the dismissal to be set aside by filing a criminal revision petition under Section 397 CrPC before either a Sessions Court or a High Court (the revisional court may look into the legality and correctness of the order passed by the Magistrate). Therefore, the complainant will have two different pathways to pursue, so as to ensure access to justice in a case of that nature, whilst also ensuring there isn’t abuse or inactivity of the officers, whether that be law enforcement or an officer of the court.

Key Developments

Indian courts have taken a proactive approach to the issues of FIRs and Complaints in recent years and in doing so, have protected the rights of the citizens.

- In the case of Lalita Kumari v. Govt. of U.P. (2013) 14 S.C.R. 713, the Supreme Court ruled that the police must register an FIR without delay in cognizable offences.

- In 2025, the Kerala High Court ruled that complaints received via email from abroad must be treated with professionalism and can lead to Zero FIRs.

- In Pavul Yesu Dhasan v. Registrar, state Human Rights Commission of Tamil Nadu (2025) INSC 677 the Supreme Court upheld that compensation was due to a person for a similarly refused FIR, further confirming the remedy available in law.

- Simultaneously, it is noted that courts quashed FIRs filing by a person way-biased and maliciously, it is very similar and consistent to the Imran Pratapgarhi v. State of Gujrat (2025) with a poem wrongfully interpreted as hate speech.

FAQs about FIR and Complaint under Indian Law

Can police refuse to register FIR?

No, for cognizable offences police has to register FIR as per orders of the Supreme Court. If police officer refuses, you have the remedy of approaching SP or file a complaint before a Magistrate u/s 156(3) of CrPC.

Can Complaint later on convert into an FIR?

Yes. If Magistrate takes cognizance of a Complaint and finds any base in law, Magistrate can order police to investigate and register FIR u/s 156(3) of CrPC.

Is FIR necessary to initiate a criminal case?

Not necessarily. Criminal proceedings can start from FIR or Complaint. However, it depends on type of offence and legal procedure chosen by aggrieved party.

Is false FIR or false Complaint punishable?

Yes. False FIR or false Complaint is punishable u/s 223 and 229 of BNS, 2023. It is punishable with imprisonment with or without fine if made with a malicious intent.

Can an FIR or Complaint be withdrawn?

An FIR for petty offences can be quashed by the High Court under Section 482 CrPC or it can be withdrawn with the permission of court. Similarly, a Complaint can also be withdrawn by the complainant before the judgment.